As always, spoilers! Day of the Tentacle was first released in 1993, so…

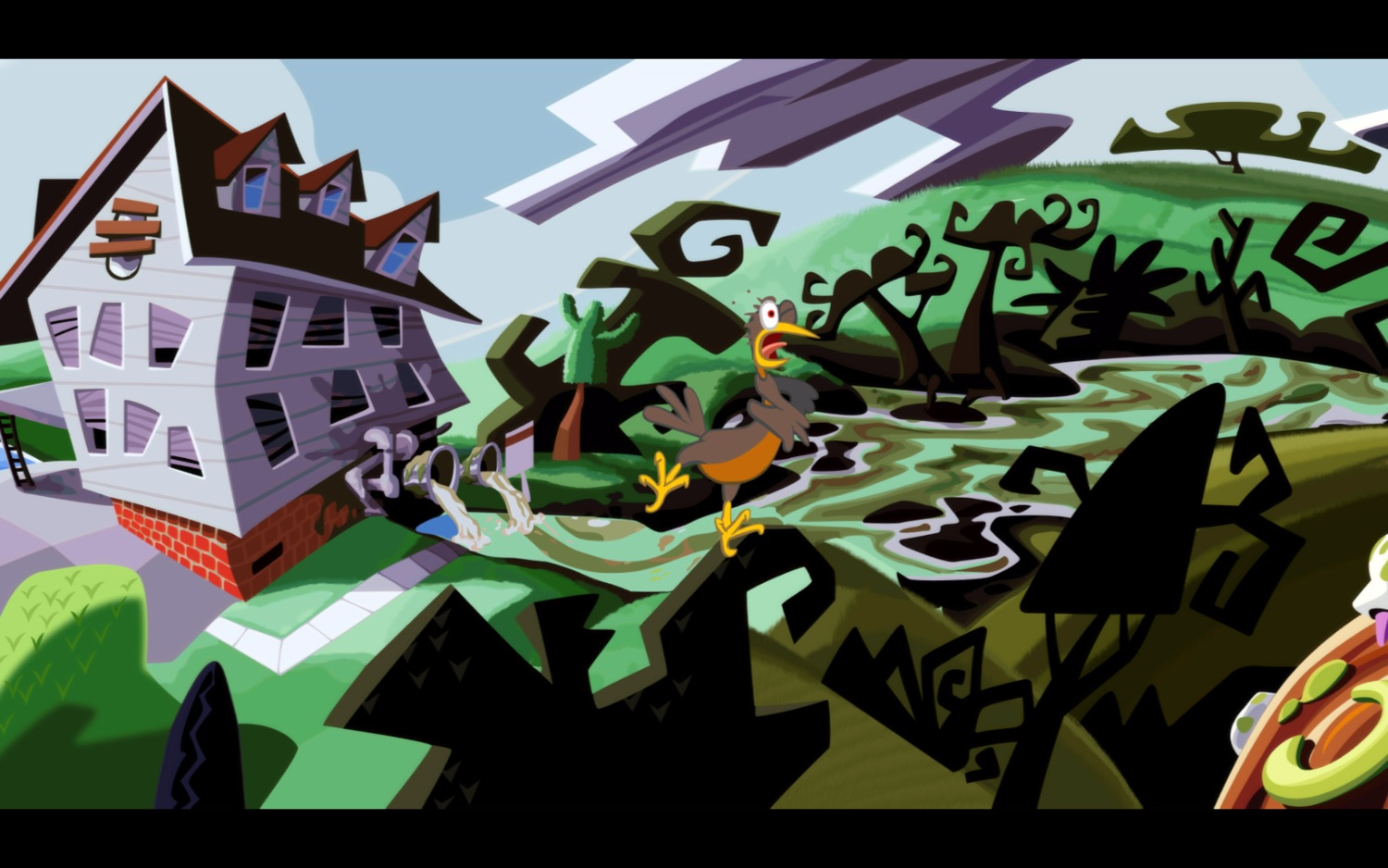

Day of the Tentacle was magical to 13-year-old me. The establishing shot of the mansion with its wild, bendy architecture was mesmerising. The thick bold lines and flat shading of Purple Tentacle as he sipped the ooze and set the story in motion was like nothing I had experienced up before in a video game.

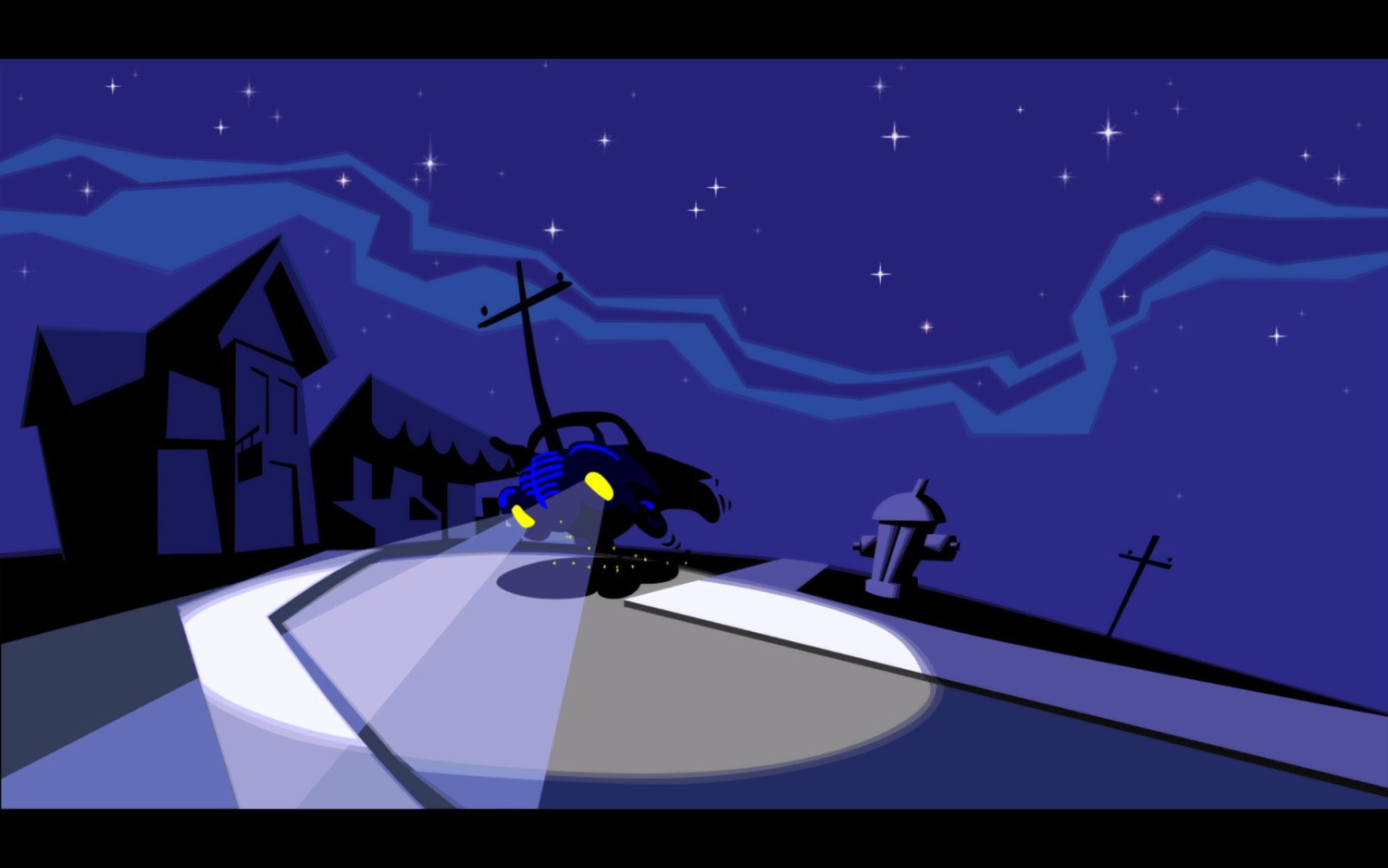

Then there was a credit sequence with the silhouette of the car, headlines blazing, leaving a trail of destruction across the countryside. It was one of the coolest things I’d ever seen on a computer screen.

The strong opening of The Secret of Monkey Island comes from its clarity of purpose and the immediacy of interaction. Day of the Tentacle, on the other hand, took its distinct visual style and coupled it with a boldness of pure storytelling—the intro alone is well over ten minutes long.

This was no accident.

The Writing

One of my favourite themes when discussing adventure games is how they balance gameplay and narrative. I’m obsessed with this. How is the player introduced to the world? Are they overwhelmed by it or does it gradually reveal itself? If it gradually reveals itself, does it feel overly restrictive? If not, how does it avoid this feeling? Do the puzzles feel natural?

That Intro

The Special Edition commentary gives us some clues. The developers of Day of the Tentacle prioritised the introduction of the world to the exclusion of almost everything else in order to get players invested in the story as quickly as possible.

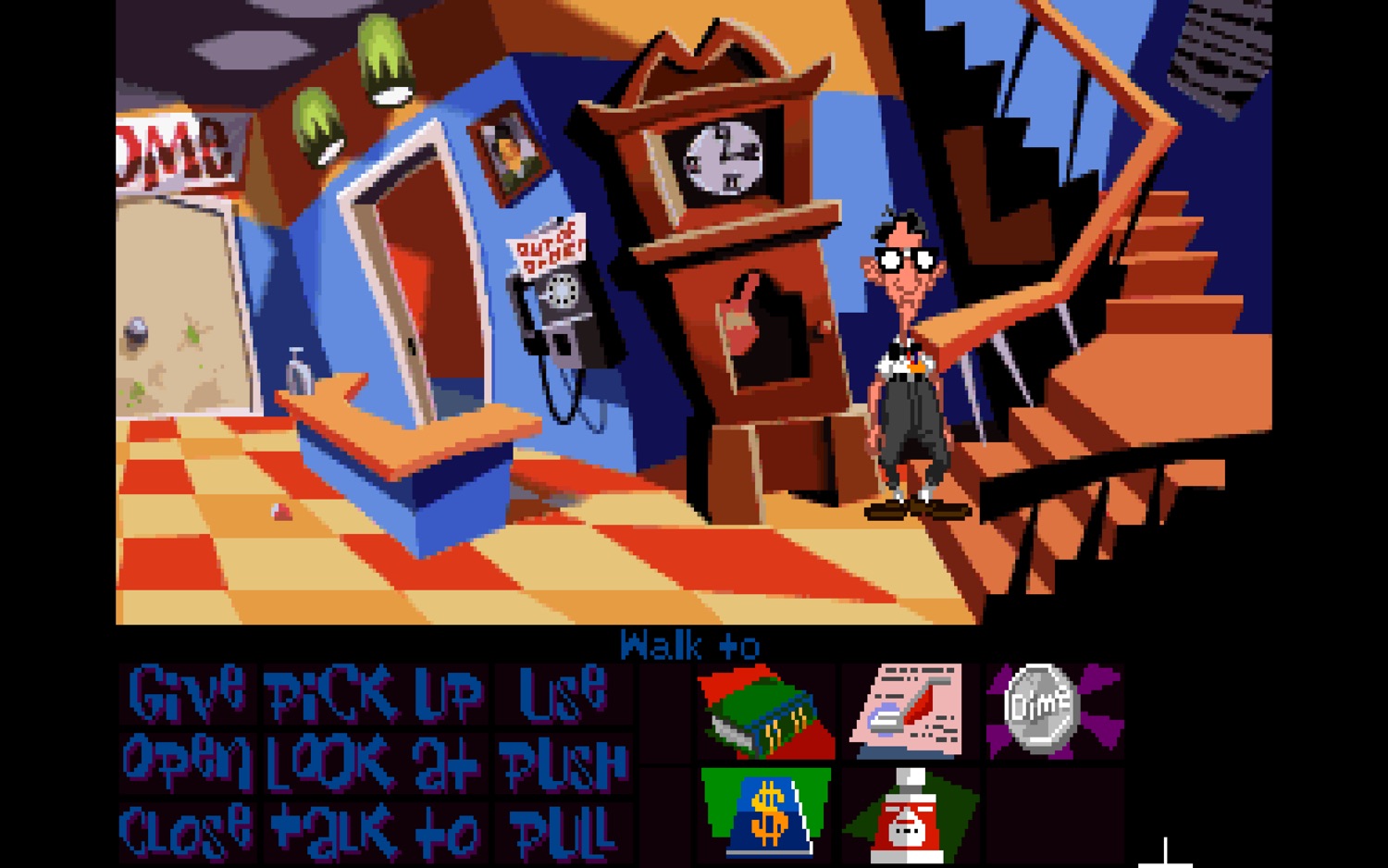

The first scene in which we are given control as Bernard and have to find Dr Fred’s laboratory was added to give players a break from the cinematic.

The nice thing about this break is that it doubles as a tutorial. A player new to adventure games would have no trouble exploring everything the first two rooms have to offer. They could quickly learn how the game works without feeling overwhelmed by too many options.

The objective of the scene is clear, and the objects and interactions available in these rooms are so limited that they could brute force the puzzle and find the solution without getting frustrated.

They then get the reward of a quick win, and the second half of the intro begins to further invest them in the story.

(Side note: I love how Dr Fred is able to easily tie up Purple Tentacle all by himself at first. Then, after the kids turn up and free him, suddenly the only way to fix it is to send the three of them through time in his new time machine…)

Now Comes The Part Where Simon Talks About Clear Objectives

In the words of Dr Fred:

I think I’ve made myself perfectly clear.

Step 1: Find plans

Step 2: Save world.

Step 3: Get out of my house!

I may have mentioned this once or twice, but I hate not knowing what I’m doing in an adventure game. I mean this both specifically (what are my immediate goals?), and generally (why am I doing any of this?).

This a LucasArts game, though, so no problems here. In fact, if anything, the above quote shows that it’s impossible to be too literal about this.

The Design

In an earlier build of the game, there were three additional characters as well as Hoagie, Laverne, and Bernard. Not only that, it was possible to play all six of these characters from the beginning.

Then the Day of the Tentacle devs did a play through and their testers said there were too many options. After this they restricted control to just Bernard initially (and ditched three of the kids completely).

Uh-Oh, He’s Going To Talk About Worlds Opening Up Again…

The staggered access to the other characters that they landed on ends up being a great example of how to manage access to the world (and a testament to the importance of testing and iteration):

- Hoagie becomes playable after we have found the plans and flushed them to him (conveniently teaching us a new mechanic at the same time).

- Laverne is available once Hoagie convinces George Washington to cut down the cherry tree, freeing her from her unfortunate tree-wedgie (but landing her in jail).

- Laverne is finally given free reign of the entire future house once she has her tentacle costume.

I will continue to repeat this so I never forget it: the best way to design adventure games is to gradually open up the available options (locations, objects, characters) while hiding the fact that you’re doing this.

The Characters

The kooky, comic book art style is a delight to behold. The sprites of the original were more pixellated than in this special edition version, but the essence shone through.

The original still looks great and has a distinctive style that continues to work for it. Unlike the special editions of The Secret of Monkey Island and Monkey Island 2, which completely overhauled the visuals of the originals, the special edition of Day of the Tentacle is more like a clearer realisation of the original’s intent.

The chaotic perspective and wild angles of objects in the backgrounds have echos of early Warner Bros cartoons, while the character shapes and personalities are unique and appropriately exaggerated.

Comic touches abound. From the cheeky smile after Laverne shoves a roller skating mummy down a ramp, to Hoagie’s butt crack as he climbs into the secret lab, there’s a ton of visual gags that take advantage of the cartoon medium.

On a more technical level, I did notice that the sprites don’t have cast shadows. However, they did get darker as they went through shadows. This is a nice touch that I’d like to use in my own games (thankfully, SpriteKit already offers this kind of dynamic colouring).

The Locations

There’s something cosy about this world. Being confined to the same building across three different time periods gives one the sense of the familiar making the differences feel even more prominent and comic and bizarre.

There is enough variety between the time periods to keep things interesting, but it feels self-contained and promises that all the answers you need are within the grounds of the mansion.

The End Game

A distinctive LucasArts technique is to add some sort of timer mechanic to the end game to ratchet up the drama (first seen in Monkey Island 2, and later again in Full Throttle).

In Day of the Tentacle, the ancient Purple Tentacle is following you with his Diminuator. He will catch you and shrink you down eventually, but this is not fatal and you quickly revert to normal size.

Solving puzzles while being chased down and shrunk repeatedly is an effective technique to heighten the tension while not resorting to any sort of death or permanent game over.

The Greatest Adventure Game?

I love this game. It’s clever and funny and looks incredible.

Watching the consequences to your actions play out across time is an absolute delight. Chopping a tree down two hundred years previous as a way to open up Laverne’s game area is immensely satisfying, and the hamster puzzles that tie together actions across time remain some of my favourites in any adventure game.

My only real criticism is that I wish it were longer. I finished it in about four hours and would have happily spent a few more hours in that world.

Then again…

Major Lesson: Get them invested in the story and leave them wanting more!