While technically a text adventure rather than a graphic adventure, it was written by Douglas Adams and it is this writing pedigree that got this game on my list.

In this department, the game doesn’t disappoint. The humour and characters set the bar high very early on for what adventure games could provide in terms of narrative and experience, foregoing the fantasy and science fiction to present a biting satirical critique on the modern world, one that still feels fresh and relevant today.

The game perfectly sends up the frustrations of dealing with those faceless corporations that we all have to battle with and time has not dulled its wit, which frankly says a lot about the sad lack of progress in our current customer service experiences.

There’s a rich vein of ideas here that could be worth mining in future, updating the game’s world but maintaining that very real sense of hopelessness—and the black and absurdist humour that arises from this—that comes from dealing with any major bureaucratic institution, only this time with graphics!

The world-weary, sarcastic voice of the the narrator also sets a tone that in some ways defines the early graphic adventure era, and echoes of it can be found everywhere from Freddy Pharkas to Manny Calavera.

Sadly, the systems within the game do not reach the promise of the premise.

Time was, reading the manual for a game was obligatory. Often, it was part of the fun. Then, when that day’s power ran out, we’d go chasing tyres with sticks.

Those days are long gone. Games learned a long time ago that it’s better to teach mechanics within the game itself, ideally as a seamless part of the narrative, than to make players read a novella first (even if it is written by an esteemed author). Introducing new mechanics as and when they’re needed is simply good design.

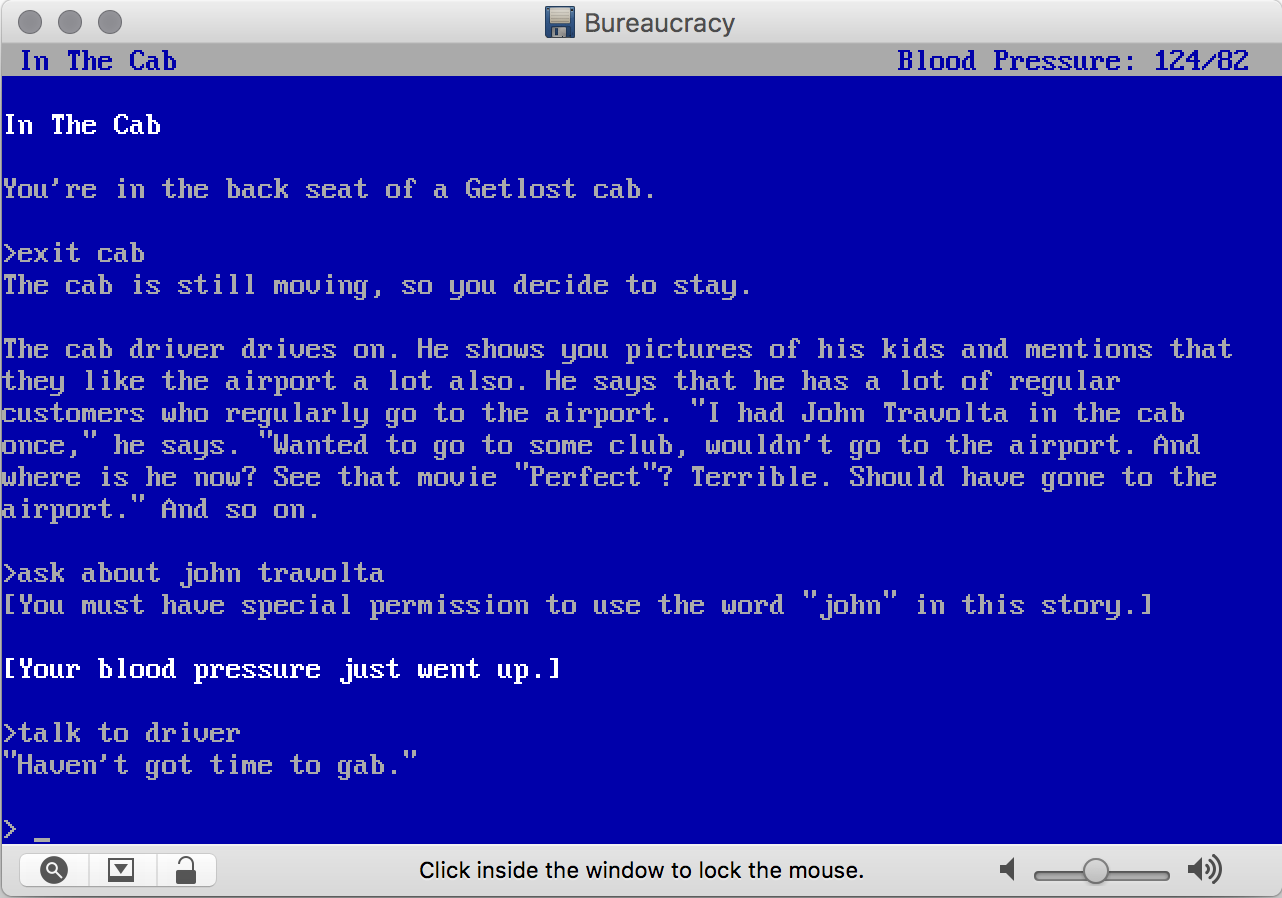

Unfortunately, here you need to read the manual to have any sort of chance with this game but, even still, many of the interaction systems are over-engineered. There are dozens and dozens of verbs and conversations are complicated and frustrating as you end up more or less having to guess what the character you’re talking to wants to hear. There’s even a pseudo-apology for this in the manual, suggesting that it’s better to interact with characters in other ways (by giving them things, for example) than just talking to them.

The health system comes in the form of blood pressure that increases if bad things happen in the game and also, bizarrely, if you make a typo. This is brutal and punishing which, if I’m generous, underlines a key part of the game’s narrative (the unsympathetic, inhuman precision required by modern institutions), but in reality it simply makes the game less fun.

It’s also obtuse and opaque. Gain too much stress and you’ll die and that’s that. It’s frustrating and there’s very little warning about what actions or interactions will cause it to go up. Another lesson well learned by games in this genre is that maybe characters don’t have to run the risk of dying in order for them to be interesting.

There is a scoring system for when you manage to take care of your physical or mental well being (for example, successfully eating food) which mostly works. There is something satisfying about getting points in addition to solving particular puzzles, and rewarding you for successful interactions in terms of a simple score is something that could maybe be used again, especially if it comes from interactions that have narrative value but don’t necessarily progress the game.

My instincts suggest that modern audiences have a lot less desire to read every branch of every dialogue tree than they once did. Offering simple achievements for doing so could make it more appealing.

The inventory system is convoluted and can be irritating to manage (it won’t necessarily infer that you want to separate items that can be separated) but, unless I see something truly innovative, inventories in adventure games are a solved problem.

Despite all these issues, the initial exploration of the town was a good experience. The writing goes a long, long way to covering a lot of the game’s shortcomings, and you get a real sense of the small English town you find yourself in and the irritable but well-drawn characters that inhabit it kept me coming back to "see" a little bit more of it.

Ultimately, though, I never made it out of the town. Or rather, I made it out of the town in a cab once and then, when I couldn’t pay the cabbie, I was driven straight back into town, at which point I gave up. Sadly, the frustrations of wrangling the arcane systems and unforgiving progression ended up outweighing the exquisite writing and I bailed after a few hours but, if you have a history with text adventures and haven’t yet seen this one, the writing along makes it well worth a look.

Bureaucracy is freely available as abandonwear and is available for MSDOS. I used Boxer on the Mac to get it up and running.