As always, this is full of spoilers!

I think about this game a lot.

I think about how it starts with a woman trying to talk calmly to a man who has tied her up and is threatening to kill her just because she had the temerity to say no and how that’s even more relevant and relatable 26 years later.

I think about the nihilism and casual violence played for laughs by the two main characters and how it captures so much about the South Park culture of the nineties (and how so much of it is still hilarious).

I think about its heart.

Wait, What?

Bear with me.

These two objectively obnoxious and dangerous eponymous characters that take nothing seriously spend the entire game running backwards and forwards across America to protect the defiant lovers Bruno and Trixie.

Then they save the dying Sasquatch culture.

Then they save the environment.

Of course, they don’t care about any of this. They’re just doing it for the chuckles. Everything is cheesy and dumb and should be made fun of, and Sam and Max are not short of amusing quips and sharp jibes.

Everything is a joke to them, yet this game is about protecting the underdogs and helping the powerless.

A Portrait of America

From the tourist trap attractions to the ridiculous caricatures of the people that run them via the nearly identical Snuckey’s that dot the highways, there is also a love of tacky Americana here.

At times it verges on intellectual sneering—there’s the overweight man dressed in the American Tourist Uniform that sits at the counter of every Snuckey’s shovelling food into his mouth—but the locations are so well realised that, like American Gods and Alice Isn’t Dead, it finds the magic of these places and delights in it.

Sam and Max are the prefect bemused bystanders to this modern America, taking the weird beings that live and work at these locations in their stride and maintaining their own brand of twisted moral compass throughout—the epitome of Chaotic Good.

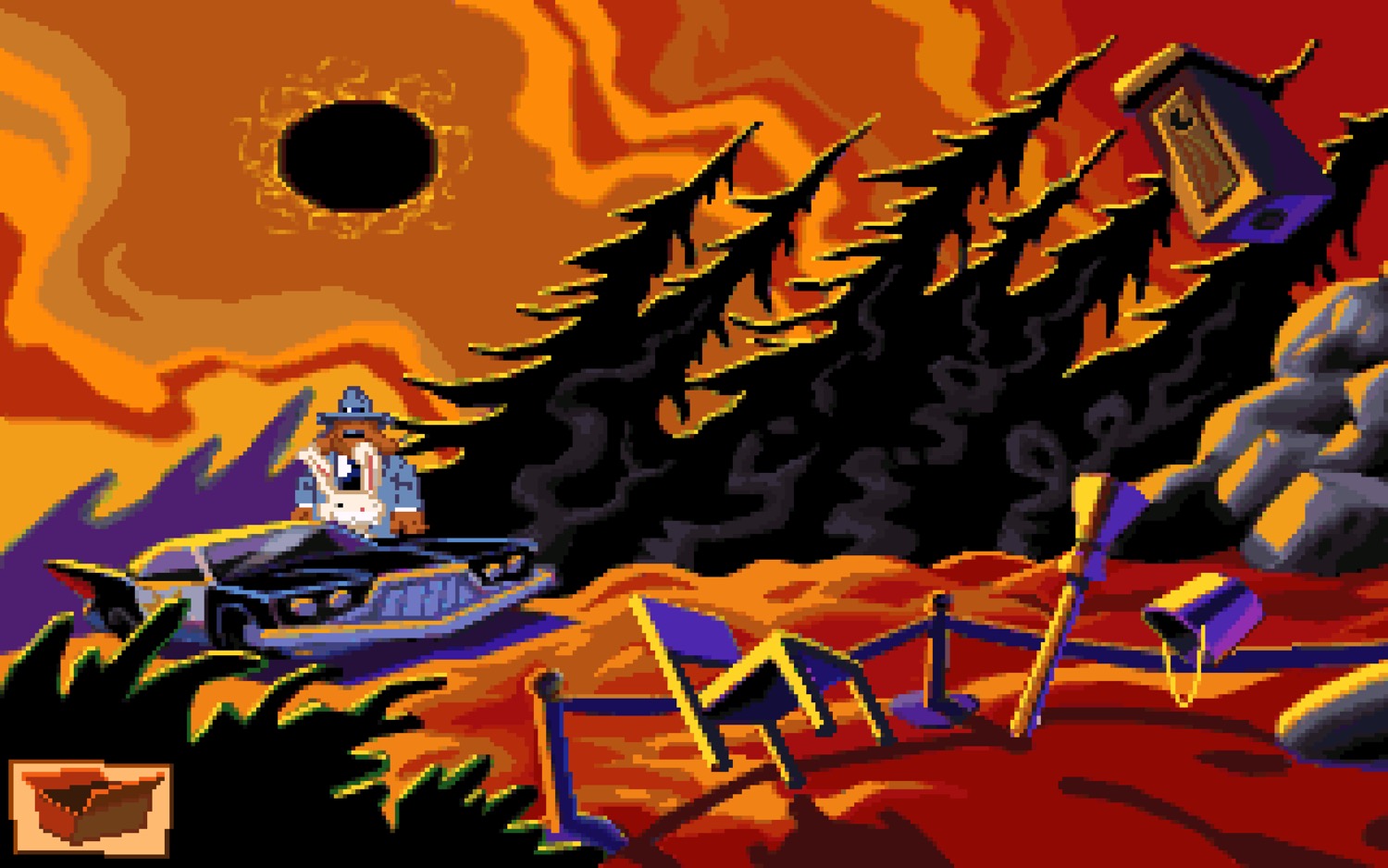

It Helps That it Looks Stunning

Sam and Max Hit the Road was the first LucasArts game to ditch the bottom third verb and inventory UI, bringing Steve Purcell’s characters and the stunning art and animations they inspired front and centre.

The available verbs made available by the looping icons of the illustrated mouse cursor are severely cut down and become more context sensitive, something that has continued to evolve within the genre to the point that the idea of separate use, push, and pull buttons now seems particulately quaint.

But this game remains a classic not just because it went full screen and looks amazing, but because these loveable carefree anti-heroes actually do measurable good in the world at a human (or rather Sasquatch-and-Giraffe-Girl) scale.

Sam and Max are are walking director’s commentaries. They are passive observers of the worlds they find themselves in, making amusing notes of the people and places they interact with, but lacking any real depth because they don’t have anything to lose.

They work best when they are attached to characters with real stakes that have nothing to do with them for the simple reason that they can’t be seen to care about anything, not even each other (in the Tunnel of Love, Sam grabs Max by the legs, dunks him in the water, then rams his head into an electric fuse box to stop the ride).

This detachment is where the comedy resides, but it means the heart of the story has to come from somewhere else—something I think the later Telltale games failed to realise.

In the Telltale games, they do go on to save the world but these later games lack the impact of Hit the Road because saving the world remains an abstract idea. It doesn’t have the intimate, relatable sincerity represented by Trixie and Bruno and the rest of the Sasquatch because even if the world did end, you can’t help but feel that Sam and Max would be fine (or at least say something funny).

This is why Sam and Max Hit the Road works. It’s a love story, and the fact that it managed to slip this in past the dismissive, derisive culture of Generation X gamers all while keeping Sam and Max true to their carefree, chaotic selves is a testament to the masterful writing and one of the major reasons that it remains an adventure game classic.

Major Lesson: Have Some Heart (But Hide It So Well They Don’t Notice For 25 Years).