Warning: As ever, spoilers about this 26 year old game abound.

Indiana Jones and the Fate of Atlantis is a 1992 action adventure game from Lucasarts, featuring everyone’s favourite adventuring academic. It adheres tightly to the Indy tropes: a mythical ancient power has the potential to give the Nazis the edge and a sceptical Indy and a credulous sidekick (Sophia) have to go on a quest to find it first (which inevitably involves a little bit of colonial grave-robbing—altogether now: where does it belong?).

It’s a surprisingly realistic portrayal of what an archeological expedition might look like. As with many real life digs, it involves a lot of foreign travel, punching, and the widespread destruction of ancient artefacts.

Punching Up and Punching Down

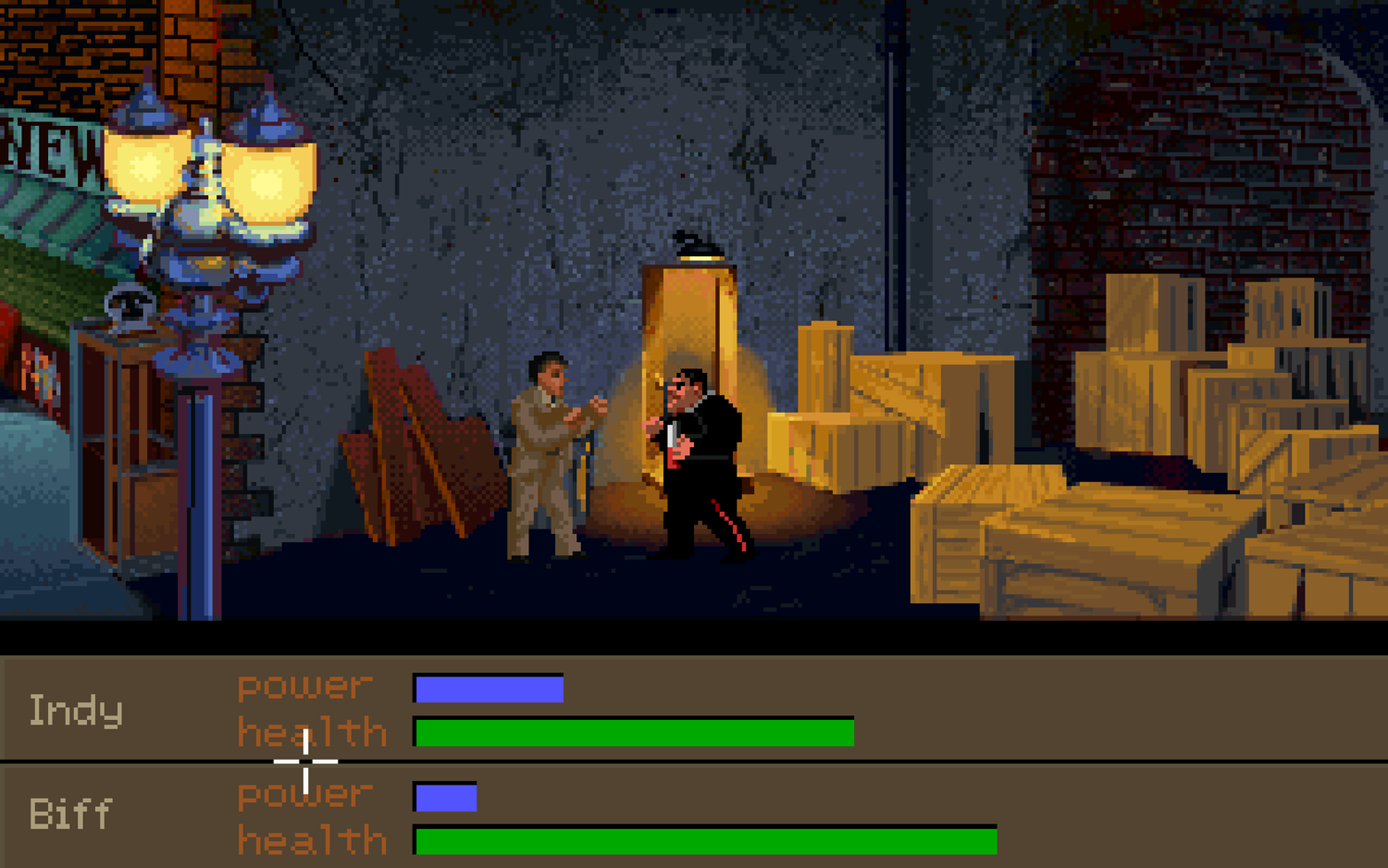

The most noticeable difference from this and other LucasArts games is the introduction of the fisticuffs mechanics, presumably because not punching Nazis in an Indy game from the 90s would be as controversial as actually punching Nazis is today.

As satisfying as it is to watch avowed fascists get their faces caved in, this mechanic has not aged well. It’s supposed to be as simple as clicking on the part of the enemy you want to punch (low, medium, high) and, should you wish, clicking the part of Indy that you want him to block.

In practice, repeated hammering of the mouse button at the other dude’s head was often enough to win. Any time I tried to fight carefully, I lost, as I found it almost impossible to block.

Like Quest for Glory IV—another adventure game that tries its hand at introducing some skill-based action elements—it isn’t quite able to get the kind of refinement needed to make these encounters satisfying and they quickly become something to be avoided if at all possible.

Thankfully, apart from an initial encounter that you can lose without dying and just repeat over and over again, you can choose a Not Punching Route where you can avoid most other encounters.

Which brings us to another interesting design choice.

I’m a Lover, not a Fighter

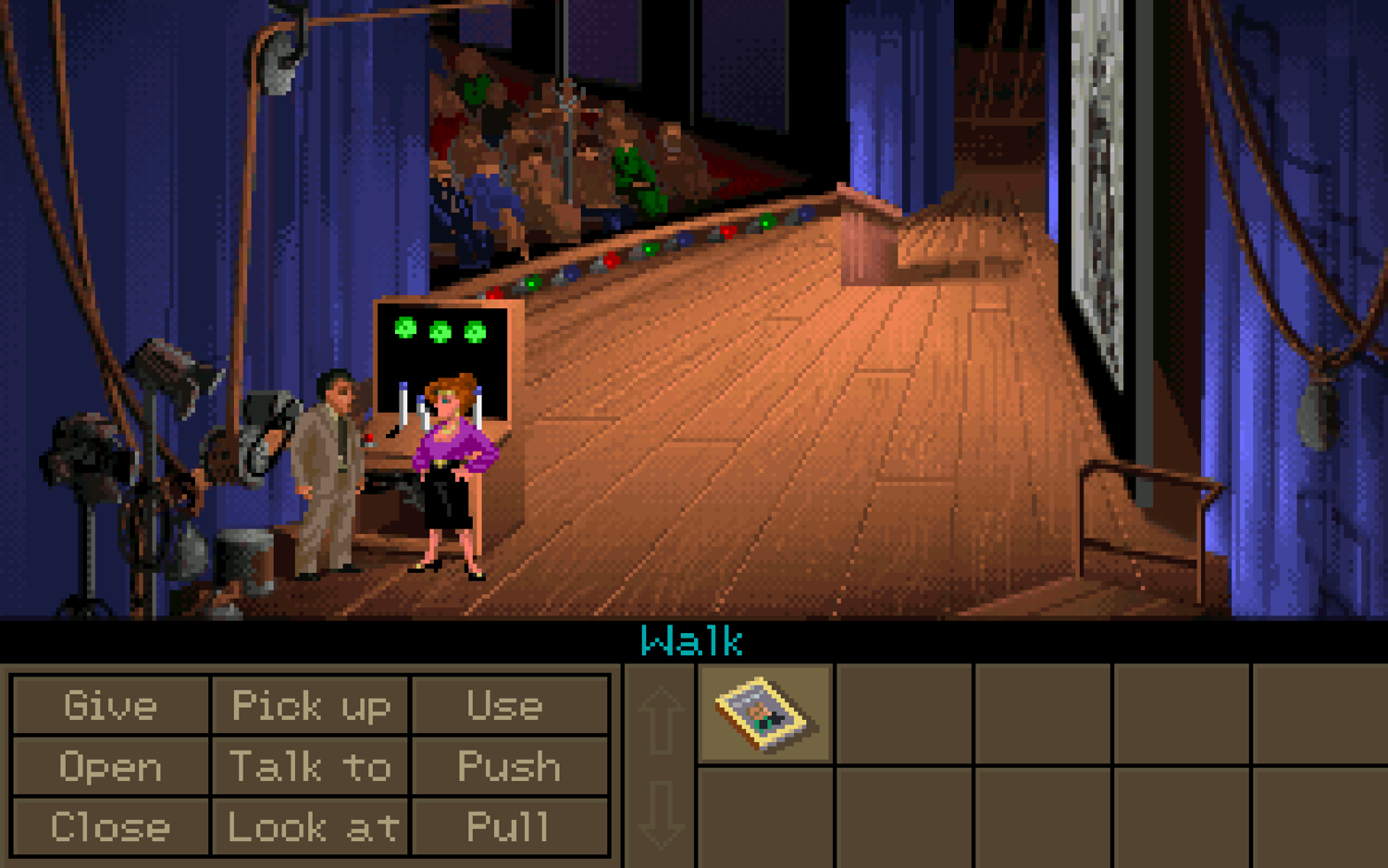

In the gentle LucasArts style, we are initially given a small area to explore and interact with and a clear objective to achieve giving us time to get used to the mechanics and get immersed in the story.

Following this, we are then presented with a choice about how we want to proceed: With just our wits, with the help of Sophia, or with fists swinging. Which one we choose will dictate the puzzles we’re exposed to.

It’s an effective way to encourage multiple playthroughs in a genre whose titles tends to have limited immediate replay value.

It does mean that, unlike other LucasArts titles, Indiana Jones and the Fate if Atlantis tends not to have multiple puzzle branches happening at the same time. Once you’ve chosen your path, there’s usually only one major puzzle that you need to solve in each location. If you get stuck, there’s no going off to solve a different puzzle and coming back to the first one later.

This isn’t too onerous as the possibility space tends to be relatively small, meaning that brute forcing it (using everything in your inventory with everything in the world) is always an option, but it does feel more limiting and on-rails than other titles.

An evolution of this idea—playing through the same locations with different puzzles each time—appears in Day of the Tentacle. The important distinction is that you can dynamically switch characters to get to the alternative versions. This gives the player the ability to pursue multiple paths at once and lessens the risk of having them hit frustrating roadblocks that they can’t leave and come back to.

The game also has a prominent points system (unusually for Lucasarts). You score Indy Quotient (IQ, see?) points, and you can only accumulate the maximum amount of points by playing through the game with all three modes (and not forgetting to do something very important near the end).

A Brief Aside About Points in Adventure Games

I see that most modern of adventure games, Kentucky Route Zero, as an evolutionary branch of the genre that drops puzzles in lieu of being entirely narrative based.

In the context of this kind of artistic ambition, points would seem like a distasteful addition, a cheap trick to measure of progress and skill that would take you out of the immersive narrative and remind you that it’s “just” a game.

You don’t collect points for noticing every subtlety in a movie or a novel.

On the other hand, there’s no doubt that points encourage further engagement in the world, especially if there are peripheral puzzles or locations that are not key to the main plot but add a satisfying additional layer. Within the strict confines of a sequential narrative like a movie, subplots are explored and resolved but, in video games, could easily be overlooked by the necessary freedom given to players.

I like the idea that points could serve as a simple reminder that there is more to be had and, if the world is compelling enough, an invitation to spend more time there.

Points systems could be used to tell players how much of the world they have seen and could open up opportunities for ‘hidden’ areas or secondary character adventures that deviate from the main plot.

While that’s not quite not what’s happening in Fate of Atlantis, its use of points to encourage replay has certainly triggered some intriguing ideas for how they might be re-introduced into modern adventure games.

Just the Once

Often in adventure games, the player’s way forward is blocked by some sort of complex environmental puzzle, such as a maze. Solving it once is part of the adventure, but having to go through it multiple times would quickly become onerous.

In Fate of Atlantis, once we’ve hacked our way through the jungle to an important location, Sophia turns up via another path and tells us there’s this shortcut, mocking our macho bravado for a quick gag into the bargain.

This is common in LucasArts games: In Monkey Island 1, finding the Sword Master gives us a new pin on the map that takes us directly there. In Monkey Island 2, Herman Toothrot shows us a shortcut after we complete a complex map puzzle.

While it might seem like naturally good design, it’s worth mentioning because in Freddy Pharkas it’s impossible to have the protagonist and his trusty sidekick not repeat their same goodbye and hello speeches every time he exited or entered his pharmacy.

However amazing a designer believes their puzzles or dialogue to be, making players repeat it more than once or twice with no quick way to skip it gets old very quickly.

Soft, Breathable Worlds

In my post about Monkey Island 2, I mentioned the expanding and contracting of worlds as a way of giving players rewards and as a way of providing variety and controlling the scope of puzzles and inventory.

This is especially evident in Fate of Atlantis and, more than many other LucasArts games except perhaps Grim Fandango, we are cut off from previous locations in relatively short order. Despite visiting locations across much of the earth, the playable areas tend to remain relatively small and self contained.

I think this is an important part of good adventure game design. It gives the feeling of progress while keeping the possibility space manageable.

Indiana Jones and the Fate of Atlantis hasn’t aged as well as other Lucasarts titles, but it remains a solid adventure game with a decent story and lots of interesting locations.

While its attempts to try new skill-based systems fall a little flat, it’s still a LucasArts adventure and, frankly, you can never have enough of those in the world.

Major Lesson: Points to point the way back through?